O’Yes

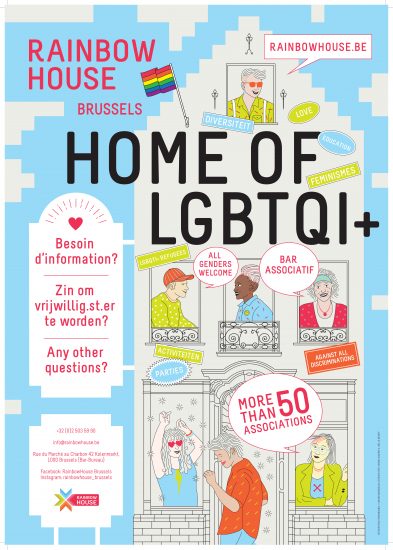

The Equalcity project is coming to an end. This project, funded by the European Union’s Rights, Equality and Citizenship programme (2014-2020), took place in Brussels at the RainbowHouse in collaboration with Equal.Brussels. It was conducted under the coordination of IOM (The International Organization for Migration) Belgium and Luxembourg from November 2019 to November 2021. The objective of the project was to build a toolbox (including awareness raising materials) to support frontline workers in existing urban services in setting up and managing safer spaces for LGBTQI+ people with a migrant background. ,.

Equalcity is a set of four toolboxes that aim to improve the reception of people with a migration background in the context of gender-based violence in the European Union. Four toolboxes are created for four different cities:

All four boxes will be available at the same time at http://iom.belgium.int/equalcity

The aim of the LGBTQI+ box is to help frontline services to be more welcoming to LGBTQI+ people with a migration background by making their services safer.

Why safer spaces?

We know that the majority of cases of sexual and gender-based violence in ‘migrant communities’ or perceived migrant communities go unreported and unaddressed. Creating safer spaces is an effective way to facilitate access to urban services for LGBTQI+ people with migrant backgrounds and encourage them to speak out without fear of repercussions and stigma by making them feel seen, heard and respected. This is a good way to empower people to seek help and trust professionals. Better practice in welcoming service users can make the difference between people walking through the door or avoiding a service altogether, sometimes at great risk. This is clearly an access issue.

There are two target audiences in this project.

Given the diversity of this public and the fact that these people working in the field often have (too) little time and means. The priority in this project was to make the tools accessible. They are therefore designed to be quickly consultable, easily understandable and contain a maximum of very practical/pragmatic advice

This group is extremely large.

People perceived as having a migration background are a heterogeneous and broad group that may include:

And while there is much talk of “THE LGBTQI+ community,” it is important to remember that the rainbow is far from homogeneous! In fact, LGBTQI+ people are lumped together under this acronym because they have similar histories and similar struggles. However, the acronym hides an infinite number of different experiences. First, because no one fits into a single category/letter. Everyone has a sexual orientation, (at least) a gender identity and expression, and gendered characteristics even when some of these are straight, cis, or dyadic. This mix already creates a lot of diversity in the community. Add to that the fact that in addition to these characteristics we have all of our other realities (disability, racialization, economic status, …) and we can conclude that the only universal commonality in the community is not being something: not being heterosexual, cisgender and/or dyadic.

So, how do we offer pragmatic advice to make our spaces safer for people with potentially diametrically opposed needs?

First, by (re)defining what a safe space is. Spaces that claim to be safe as they are often imagined collectively and without a precise definition suffer from 3 main problems:

Please note: Safe does not mean comfortable and it is possible to be challenged and even disagree in a safe way.

A safe space is a space :

– accepting and respectful of each other’s identities,

– where you can share information about yourself without fear of negative repercussions.

– that challenges social norms and prejudices, even in the form of microaggressions.

– in which people feel safe enough physically, psychologically and emotionally to take risks, express and explore their views, identities, attitudes and behaviours.

We will even talk about (more) safe space because it is clear that it is impossible to guarantee a 100% safe space, 100% of the time. First of all because, as already mentioned, space has less to do with the place than with the interactions that take place there and therefore with the people who are there, which change regularly. But also because these people are human and there is nothing more human than making mistakes. Sometimes we make mistakes, things don’t turn out the way we want them to, even with the best of intentions.

This vision of safe spaces has its roots in black feminist theories and practices, particularly in the United States. In this context, safe spaces are seen as a tool for social justice and the deconstruction of power imbalances, including the imbalance between those who are perceived as helpers and those who are perceived as needing help.

In order to make the advice in this toolkit as relevant as possible despite the wide diversity of the target audiences (frontline workers and LGBTQIA+ people of migrant background), we have chosen to focus on three key principles that serve as a common thread:

In the toolkit; the focus is on 3 fundamental elements of safe spaces:

The toolkit is (going to be) available free of charge in English, French, Dutch and Portuguese at https://belgium.iom.int/equalcity and contains four main documents:

It is accompanied by a guide for local cities/authorities and an awareness campaign with posters/flyers and the videos you can see (below or by following this link)

Because you are important ! RainbowHouse launches its first communication survey with the goal of optimizing the diffusion of information...

publié le 29 September 2017

The new report by TGEU (Transgender Europe) has just been released. It is a detailed analysis of the situation of...

publié le 29 September 2017

The Equalcity project is coming to an end. This project, funded by the European Union’s Rights, Equality and Citizenship programme...

publié le 29 September 2017

The new report by TGEU (Transgender Europe) has just been released. It is a detailed analysis of the situation of...

publié le 29 September 2017